Large areas of the world’s temperate shores are fringed by marshes. Too cold for mangroves, these are dominated by shrubs, herbs or grasses, growing over deep mud and cut through by myriad winding channels. Although exposed to the air for much of the day, they are occasionally covered by tides. Countless fish and shellfish benefit from their shelter and their rich productivity.

While saltmarshes lack the high physical structures of mangroves, for smaller waves and surges their dense vegetation actually makes them more effective in wave attenuation. The tightly packed vegetation creates strong frictional resistance to waves, while both the aboveground plants and their dense root systems help to stabilize sediments and reduce erosion.

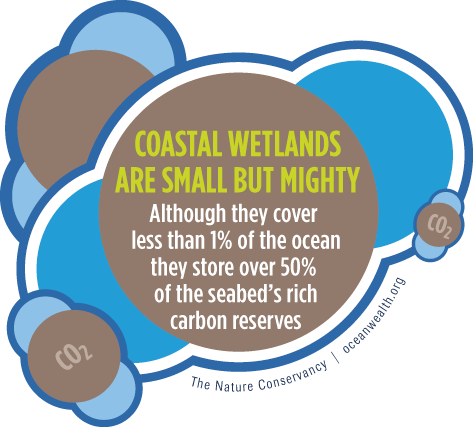

Intertidal saltmarshes were left out of carbon models for years, but ecologists have long known that they were among the most productive ecosystems on earth. Increasingly, studies are also finding deep layers of centuries-old, carbon-rich soil beneath this habitat. Despite their importance, however, we still lack reliable global maps of both saltmarshes With this uncertainty, we are unable to accurately predict their global role in carbon cycles and climate change, but research at local scales are impressive and should spark further study.

Explore Saltmarsh Ecosystem Services

Top image: © Karine Aigner. Photo Credits: © Mark Godfrey, © Jonathan Kerr, © Nick Hall