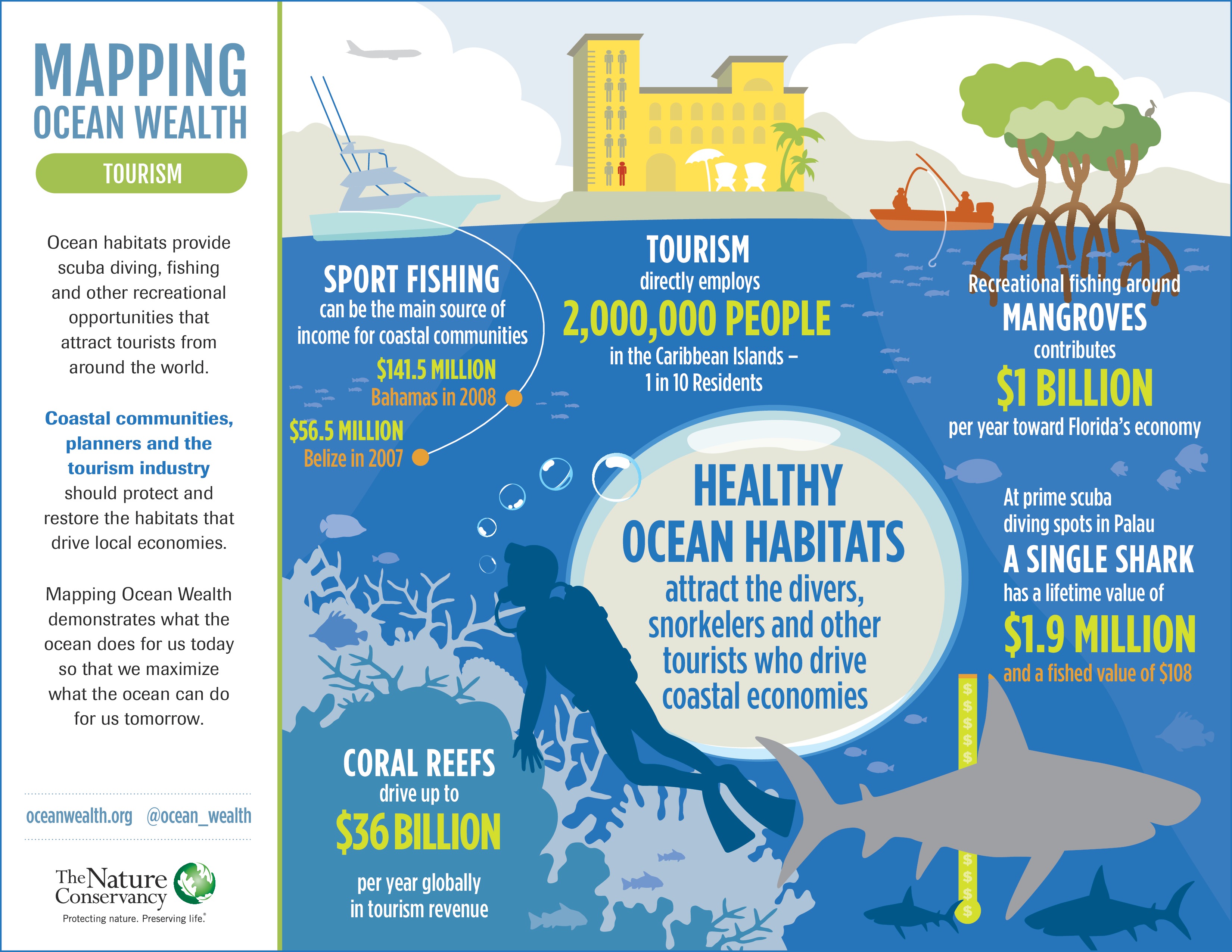

Offering clean, calm water, pristine beaches, superlative seafood and stunning vistas, coral reefs and other marine and coastal ecosystems form the land and seascape that many tourists, consciously or unconsciously, have come to enjoy

Benefits of nature based tourism

- Over 350 million people annually travel to the coral reef coast of the world

- The coral reef tourism sector is has an estimated annual value of $36 billion

- Over 70 countries and territories have “million dollar reefs” — reefs that generate over $1 million in tourism spending annually

- 600,000 people have been estimated to spend over US $30 million annually to watch sharks

Our Projects

Mapping nature-dependent tourism presents novel challenges. Value is not solely driven by ecology, but by a complex interaction of history, culture, infrastructure, politics and economics. The development of predictive models is therefore challenging, but at the same time, vast amounts of data—from government statistics to hotel and airline data—are available to support the development of actual maps of use and value. Mapping Ocean Wealth has been able to work with others on novel approaches to draw information from social media and crowd-sourced databases to provide indicators of tourist activities. We have used a variety of these to develop unique approaches to map nature-dependent tourism at global scales.

Fine Scale Mapping of Tourism and Recreation

Tourism and recreation in coastal states and regions is often highly dependent on nature. This includes nature-based activities, such as diving on coral reefs, hiking or bird-watching, but also many aspects of travel or recreation where nature may not appear, at first glance, to play a role. The pleasure of locally caught, fresh seafood, for example has an immense value. Likewise, destination choice is often shaped by images – and hotel rooms chosen by views – where nature is often up front and central. White sand beaches, clear waters, forested hills and fresh snapper for dinner may all be critical in driving choice and spending. Protecting those values is a necessity for the industry to remain sustainable, but all too often, there are few facts, or maps, to support decision makers.

The Nature Conservancy is breaking new ground in telling the full story of nature dependency in the tourism and recreation sector. In a highly innovative project based across five nations in the Eastern Caribbean we have mapped value for several aspects of nature dependency:

- On reef activities

- Nature dependent beaches

- Paddle sports

- Recreational/sports fishing

- Whale and dolphin watching

- Birdwatching

- Seafood restaurants

The underlying approach for all of this work involved a unique combination of utilising existing data from very large public sources – including an important collaboration with the online travel platform TripAdvisor – and extensive local outreach and knowledge. Initial parsing of very large volumes of information was undertaken using both image and text recognition filtering and included valued support from Microsoft’s AI for Earth team. In this way some 90,000 independent data points were developed showing locations where nature is supporting tourism and recreation.

More information, including details of the individual models can be found here oceanwealth.org/project-areas/caribbean/crop/ and the maps themselves can be explored here oceanwealth.org/oecs/. Reports and a peer reviewed publication can be located here oceanwealth.org/resources/research-library/

Similar approaches have also been used to understand nature dependency in tourism in the Seychelles, https://oceanwealth.org/project-areas/seychelles/ where the information are already being utilised in ongoing Marine Spatial Planning exercises, and new work using these techniques is underway.

Global Coral Reef Tourism

Our global map of coastal tourism in the tropics is built from a unique and highly innovative approach in which we pulled together multiple large datasets and used these to build, correct and refine one another. Our starting point was national statistics on tourist arrivals and spending, including both national and international tourists and visitors. Our first stage was to separate out the coastal component of these numbers. We used two large datasets to understand the spread of visitors: first, data from over 125,000 hotels, including location and hotel size; and, second, the geographic location of photographs uploaded onto the social media site, Flickr. These two layers both provide independent estimates for visitation and use and we combined them with the coral reef map to filter the national tourism statistics, and to capture only those areas away from large towns and cities, within two kilometers of the coast and within 30 kilometers of a coral reef. View interactive map.

Clearly only part of the tourism close to coral reefs is linked to the reefs. We conservatively assigned 10 percent of this tourism expenditure to what we called “reef adjacent” tourism. This is the “added value” we consider that reefs bring through the provision of calm water, white-sand beaches, top seafood and beautiful views. We then developed an estimate focused specifically on the “on-reef” tourism. This is the direct “use” of reefs, primarily for diving and snorkeling. We estimated this using two further datasets: the location of dive shops/centers and the location of underwater photographs on Flickr. Both independently, help us to approximate the amount of “on-reef” activities. For instance, where there are higher numbers of dive centers per hotel, or where underwater photos make up a higher proportion of all photos. We can then infer that diving and snorkeling will be an important part of the tourism agenda.

The final stage of the mapping work was to link the values of the two components of tourism back out to the reefs that provide this value. We used a combination of proximity measures (for the reef-adjacent values) and direct-use locations derived from both the underwater photos and from large crowd-sourced datasets of dive sites worldwide.

The results show many reefs (about 70 percent of the world total) are likely not important for coral reef tourism, but elsewhere the values are highly variable. Many leading coral reef tourism destinations are developing economies such as the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Belize or Honduras. Many are also small island nations with few other economic alternatives. For them, reef tourism is a lifeline, giving a critical boost to local economies.

Currently, the MOW team is working on a project to refine these results using a combination of machine learning and artificial intelligence, and enhanced social media scraping techniques. Through a partnership with Microsoft and Esri, the MOW team is using image recognition to identify underwater photographs that have been uploaded to Flickr. In the original model, underwater images from Flickr were identified based on tags manually inserted by Flickr users. The team anticipates that using image recognition techniques will result in a more robust input dataset, leading to more accurate model results.

In a related project, JetBlue and the World Travel and Tourism Council supported work to refine the estimates of reef-adjacent tourism in the Caribbean by using a combination of a literature review and social media to devise national estimates on the importance of coral reefs to reef-adjacent activities. In the original model, reef-adjacent tourism was assigned a value of 10% across all jurisdictions. This project refined that approach by using a combination of social media content, layered with traditionally sourced data from government agencies and the tourism industry to refine estimates of reef adjacent tourism that vary by country. Read more in the report and project summary.

Mangrove Tourism

For our work on mangrove tourism, we turned to the popular travel website, TripAdvisor, to search for mangrove related “attractions.” A key part of our interest in using TripAdvisor was to look beyond simply where people are visiting these ecosystems, and to explore what they might be doing there. We were able, for example, to call out reviews of attractions that had keywords in, such as boardwalk, visitor center, kayaking and so on.

The global reach of mangrove tourism is extensive, with almost 4,000 attractions in 93 countries listed as having mangroves. Many sites have hundreds of individual reviews. The number of reviews may be some indication of visitation, but they can also be searched to find activities, which include kayaking, wildlife tours, boardwalks and fishing. Inset shows the distribution around the eastern Caribbean Sea.

While mangrove tourism is unlikely to compete with some of the larger mass-tourism attractions, this initial work provides a critical caution to coastal developers, and highlights potential opportunities. Mangroves have many values and adding tourism to the list may help countries to secure a future for a habitat that also feeds, protects and stores carbon. Read the full study here. View map here.

Recreational fishing

Recreational fishing in coastal and offshore waters is a globally distributed, high-value activity with numerous benefits such as health, wellbeing, jobs, income, travel, accommodation, and conservation. There are an estimated 220 million recreational fishers in the world, greatly outnumbering commercial fishers in many countries. Even so, recreational fishing’s contribution to total catches is small compared to commercial fish catches, with marine recreational catch estimated at 900,000 tonnes in 2014. Despite lower overall catches at global scales, unsustainable practices in recreational fishing can have impacts on ecosystems and social and economic benefits. It is therefore critical to understand and communicate the value of such fisheries, as a means to support enhanced management and to generate ongoing benefits for fishers, ecosystems and coastal communities.

A study led by Ball State University and The Nature Conservancy explores new methods for quantifying and valuing recreational fishing, focusing on user-generated content from fishers and key market suppliers. A key data source for this work was one of the world’s biggest recreational fisher apps. Such apps are used by fishers to help them to choose fishing destinations, provide a sort of journal of their catches, and probably also give them a sort of bragging tool. With colleagues in Ball State University, we worked with over ten years of catch records which we shaved down to look at marine and brackish species caught in coastal and offshore waters. The report and maps can be found here.

Wildlife Watching

The oceans are home to the largest organisms on earth, and to some of the most spectacular gatherings of wildlife to be seen. Since the 1990s, there has been a remarkable transformation of public attitudes towards marine life. Access to places, from coral reefs to polar icecaps, where people can experience the abundance and the activities of nature up close has risen at rates far greater than overall increases in tourism.

At the same time, interest in marine megafauna such as sharks, whales, dolphins and turtles has boomed. While some of these animals are still hunted, their value to fishers is dwarfed in many areas by their potential value in the tourism industry when they are alive. As an example, some 600,000 people have been estimated to spend over US$300 million annually to watch sharks, securing some 10,000 jobs worldwide. Worked down to individual locations, such values can be incredible. In Palau, for instance, an estimated population of 100 sharks are supporting $18 million worth of shark diving each year.

The Mapping Ocean Wealth team is exploring the value of wildlife viewing tourism at the regional level. Read more here about our work in the Gulf of California.

Additional Information

Ecosystems

Top image: ©Ami Vitale. Photo Credits in Text: © Christiana Ferris, © Jason Houston, © Jeff Yonover. Tiles (left to right): © Jeff Yonover, © Tim Calver