Habitat, Fish and Profit: Combining Fisheries Ecology and Economy

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row” make_fullwidth=”off” use_custom_width=”off” width_unit=”on” use_custom_gutter=”off” padding_mobile=”off” allow_player_pause=”off” parallax=”off” parallax_method=”off” make_equal=”off” parallax_1=”off” parallax_method_1=”off” column_padding_mobile=”on”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Main Content” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Contributed by Andrew Frederick Johnson (1), Marcia Moreno-Bàez (2), Andrès Cisneros-Montemayor (3), Alfredo Girón-Nava (1), Alvin Suàrez Castillo(4) and Octavio Aburto Oropeza (1)

The value of nature and its contribution to human well being and development is being increasingly appreciated by researchers, communities and governments. Calculating the economic benefits of an ecosystem service in order to justify the sustainable use and/or conservation of a resource or area is often necessary to justify the actual cost of conservation action, but it is not easy. It takes scientists, economists and potentially sociologists and engineers working together in complex systems, sometimes over long periods of time where there could be little or no data.

Considering the often large spatial scales involved, blurred national boundaries and many unknowns present in marine ecosystems globally, the aforementioned tasks prove a considerable challenge to conservation science.

The Gulf of California (the Sea of Cortez) between the Baja California peninsular and the Mexican Mainland is an area of outstanding marine diversity, productivity and economic importance. Marine fisheries in the region account for 70% of Mexico’s total fisheries catches and coastal ecotourism is booming with improvements in transport infrastructure coming to a once isolated region. The story is not, however, all rose-tinted. The majority (60%) of Mexican fish stocks are fished at or above sustainable levels threatening both ecological and economic stability of this large marine ecosystem.

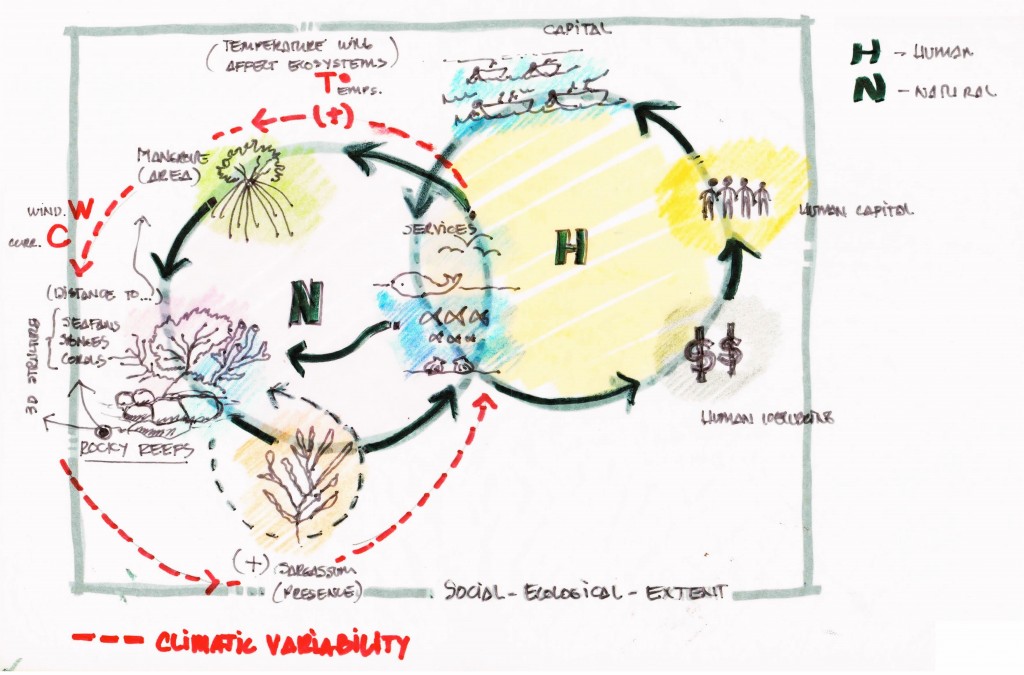

Many fish species rely on different habitats dependent on their life-cycle stage. Juveniles often confine themselves to structurally complex habitats where they can find shelter and feed, moving further offshore when they are large enough to evade common predations.

In the Gulf of California the knotted, complex roots systems of mangrove forests provide sanctuary for the juveniles of many commercial species, which migrate to rocky reefs during their adult lives. For species following this life-cycle pattern, the abundance and health of such habitats, including Sargasso beds, are directly linked to adult population numbers and are echoed clearly in fisheries catches. A healthier habitat means more, healthy fish and therefore more opportunities for productive fisheries. This ultimately leads to better local and regional livelihoods and economies.

In collaboration with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Gulf of California Marine Program at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego is currently working to calculate the wealth of fisheries in the Gulf of California. Calculating the wealth of a resource from past fisheries catch involves simple conversions of biomass from fish catches into economic values, using historic market prices. The project, however, aims to calculate future wealth of fisheries from the Gulf of California based on these past data. This is not such a simple story. It involves translating the amount of recruitment habitat into commercially viable fish populations, primarily accounting for natural mortality and exploitation rates from the fishery. Future market prices can be estimated from historic patterns in supply and demand. An additionally important consideration in the Gulf of California is the climate variability and how it impacts fish populations—particularly El Niño events.

Since the start of the project in early 2015, the team has collated data for the historic commercial fisheries from the last 15 years, habitat extent and market prices data. The team has also designed a method of estimating the fishing pressure throughout the Gulf, which will be applied to the geographic habitat information, and will illustrate how different areas of habitat are impacted by the Gulf’s fishing fleets.

The final outcomes from the project will be a series of map layers that can be used, through a series of model constructions, to calculate the wealth of Gulf fisheries historically, today and in the near future. These map layers will be made available through the Mapping Ocean Wealth portal for stakeholders, decision-makers and the general public to visualize comparisons and tradeoffs when it comes to making decisions about shoreline conversion from fish habitat to human developments, for example. Such information can be used to highlight the importance of conserving species and habitat not only ecologically, but also economically, which often has more weight with policy and government decision makers.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”For more on this subject:” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” custom_css_main_element=”border-top: 1px black solid;||padding-top: 25px;”]

For more on this subject:

Download and read Role of Mangroves in Fisheries Enhancement. Spalding et al (2014)

Read Climatic Influence on Reef Fish Recruitment and Fisheries. Oropeza et al. (2010) Mar. Prog. Ecol. Ser.

Read Mangroves in the Gulf of California Increase Fishery Yields. Aburto-Oropeza et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (2008)

Learn more about Scripps Institute of Oceanography Gulf of California Marine Program on Facebook Page or follow them on Twitter

Learn more about dataMares on the dataMares Facebook Page or follow them on TWITTER

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”foot notes” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” custom_css_main_element=”border-top: 1px black solid;||padding-top: 25px;”]

(1) Scripps Institute of Oceanography – a Mapping Ocean Wealth Partner

(2) Centro para la Biodiversidad Marina y la Conservación, La Paz, Mexico

(3) NEREUS Program/Fisheries Economics Research Unit, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada,

(4) Comunidad y Biodiversidad, COBI, Mexico

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]